Clint Eastwood has for decades embodied red-blooded, red-state

American manhood, but under that persona evolved a soulful, deeply humane

perspective on the sexes that has blossomed into a late, great filmmaking

adventure. I recently discovered this piece whilst I was researching for a

class presentation on equality and diversity within Eastwood’s films. It’s a

piece by Karen Durbin for ELLE that was originally published on October 25th,

2010. I thought I’d reproduce it here as I found it to be a very enjoyable

read. I’ve also enhanced it with some photos relevant to the story.

Channel surfing one lazy

afternoon in the '90s, I was stopped in my tracks at the sight of Clint

Eastwood on the hot seat in John McLaughlin's One on One interview show.

McLaughlin is best known as the irascible, right-leaning host of The McLaughlin

Group, a weekly Washington, DC, journalists' free-for-all. That day, thrilled

to have such a spectacular guest all to himself, McLaughlin was pitching

softballs. But as in the fable of the scorpion and the frog, his true nature suddenly

erupted, and, fixing Eastwood with a suspicious glare, he barked, "Some

people say your movies have a hidden feminist agenda. Is that true?" His

eyes dancing with delight, Eastwood could barely keep a straight face, finally

saying, "The only agenda I have for my movies is they should be

good."

Well, sure, but funnily enough,

McLaughlin was on to something. Recalling the show today, Eastwood says, "Everybody's always trying to put a

spin on what a person is or what they do. When I was growing up, George Cukor

was known as a women's director, primarily because his movies had great female

leads. But Howard Hawks did wonderful movies such as His Girl Friday, and he

was considered a man's director." Eastwood has proved to be both. I

think a feminist element entered his work almost 40 years ago and made it

better. It's not an ideological thing, nor does it need to be.

A gut sense of fairness toward

women and a camaraderie built on empathy and respect will do just fine.

Eastwood has become a

woman-friendly director because he's actually interested in us. In his recent

films, the sexes take turns on centre stage, from Million Dollar Baby (Hilary

Swank as a young woman hoping to box her way out of poverty) to the Iwo Jima

war films, then Changeling (Angelina Jolie as a 1920s mother who loses her

child under corrupt and horrific circumstances), then Gran Torino (Eastwood as

a crusty bigot able to change) and Invictus (with his good buddy Morgan Freeman

as Nelson Mandela).

In his new film, Hereafter, the

twain meet again, with the lovely Belgian actress Cecile de France as a

journalist trapped underwater by a lethal tsunami, then almost miraculously

returned to life, and Matt Damon as a reluctant psychic who can communicate

with the dead but longs desperately to be normal. Bryce Dallas Howard puts in a

luminous appearance too, and so do little identical British twin brothers.

The supernatural theme in

Hereafter is subtle, although the movie's inspired description of the

afterlife is something to savour. But the film's real subject and the source of

its emotional power is that terrible thing we all face: not our own death, but

the deaths of those we love. Eastwood, who just turned 80, treats this subject

with uncommon grace. Age hasn't made him maudlin, just deft. Talking about

working with him for the first time, de France says, "Every day he would put his hand on my head—he's very cool, very

tender. He really emanates love. Watching him work, I thought I really would

like to be in his skin. He's happy, and he's found serenity in himself."

The supernatural theme in

Hereafter is subtle, although the movie's inspired description of the

afterlife is something to savour. But the film's real subject and the source of

its emotional power is that terrible thing we all face: not our own death, but

the deaths of those we love. Eastwood, who just turned 80, treats this subject

with uncommon grace. Age hasn't made him maudlin, just deft. Talking about

working with him for the first time, de France says, "Every day he would put his hand on my head—he's very cool, very

tender. He really emanates love. Watching him work, I thought I really would

like to be in his skin. He's happy, and he's found serenity in himself."

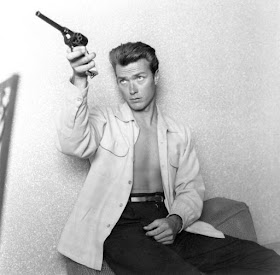

Does that sound like Dirty Harry

to you? Over the years, Eastwood has evolved as few actors have into one of the

true—and most versatile—artists of American cinema: acting, directing,

producing—even composing the music for some of his films. But before any of

this happened, he became a world-famous icon of industrial-strength machismo by

playing two characters. In the mid-'60s, he was the Man With No Name, a

roughneck serape-wearing cowboy in a trio of Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns, a

character he gave an allegorical tinge to in 1973 in High Plains Drifter, his

third movie as a director. A tale of vengeful salvation, it contains a scene in

which his character, dubbed the Stranger, makes a point of raping a woman—an

awful woman in the awful town that he's ruthlessly setting to rights, but rape

is rape. By that time, the '70s backlash against the transformative '60s had

set in. The Man with No Name had an urban counterpart in Dirty Harry Callahan,

a Magnum-flashing San Francisco cop who shoots the bad guys and gets in trouble

with the city's Constitution-quoting liberals.

The Dirty Harry movies were glib,

nasty, and maliciously false; they're not just silly dick flicks but a

relentless attack on the Bill of Rights: Judges don't gloat at letting

murderers go free, and DAs don't love tying cops' hands. Once the mayor of

Carmel, California, Eastwood genuinely cares about the health of the body

politic, and whatever he thought about those films at the time (he was past 40

and they made him a huge star) his fans' reactions made him uneasy.

"People are always trying to equate you with the roles you play.

When you start going out and diversifying, they say, `Wait a minute, why is he

doing this?' In my earlier years, I found that people would be disappointed if

I didn't pull out a .45 Magnum." He sounds even more uneasy today

about the country at large. "We're

at a point now where nobody can have a political discussion without calling

each other meatheads and idiots," he says. "In the old days you

discussed things. I guess we were more liberal then. Now it seems that no one

is interested in that. It's very frightening."

Luckily, Eastwood had already

begun to diversify, and his first effort as a director, Play Misty for Me

(1971), immediately drew complaints. The beautiful Jessica Walter—known today

as the mean mom in Arrested Development—plays Evelyn, a fling of Eastwood's

late-night DJ who becomes his lethal stalker. Via e-mail, Walter says,

"We decided we shouldn't know anything

about her because it would be scarier that way."

It is. Evelyn is

truly frightening, but she's familiar, too. Who hasn't gone postal on a man and

felt mortified afterward? Eastwood's camera never mocks Evelyn. Walter shows us

her painful fear and confusion; her eyes widen anxiously as paranoia sweeps

over her like a veil, erasing any trace of sanity and culminating in

off-the-leash rage. You can't help feeling relieved at her death; it's an end

to her suffering as well.

"Forty years ago, people were very conscious of feminism,"

Eastwood says. "The first picture I

directed had Jessica Walter's wonderful performance in a wonderful role, and I

had feminists saying, `Why are you so oppressive to women?' At the same time,

one of the executives at Universal asked me, `Why would Clint Eastwood want to

make a movie where a woman had the best role?' "

Eastwood's oeuvre soon became

studded with rich, prominent roles for women, and this time, virtue was

rewarded. Five years ago, Million Dollar Baby brought Eastwood Oscars for best

director and best picture, another to Hilary Swank for best actress, and one

for Morgan Freeman for best supporting actor. The story portrays Maggie

Fitzgerald's dogged quest to become a boxer. Eastwood, as the aging trainer

Frankie Dunn, unpleasantly points out, "I don't train girls."

Eventually he does, of course, and the decision profoundly alters his life.

Eastwood and Swank carry equal weight in this movie, but her performance goes

so deep it's impossible to imagine anyone else in the role. Swank puts it all

on him, of course. "It's his great

belief in you that lets you jump off the cliff," she says. "Yet you have to have a safety net, and

Clint gives that to you by making the set a very safe place in which to

work."

Perhaps the most surprising thing

about Eastwood is how romantic he can be, off screen as well as on. Known in

his jazz-playing youth as a ladies' man not unlike the DJ in Misty, he's now a

paterfamilias in spades and revels in it. He has seven children with five

women, bookended by marriages. His first union, a young actor and model's heady

impulse, lasted for more than three decades; the second began when TV

journalist Dina Ruiz interviewed him, and they're still going strong. His

daughter with the actress Frances Fisher lives with him and Dina and their

daughter during the school year because Monterey beats L.A. as a place to raise

a kid. And he speaks with palpable pleasure about his son Scott, now 24, whom

he introduced to music early on and who is now dedicated to it in a way that,

Eastwood says wistfully, he and his Depression-era dad couldn't be. If his

approach to family is more countercultural than nuclear, then judging by the

lack of gossip and bitter tell-all books emanating from the arrangement,

everybody seems reasonably content. (In the '80s, however, following her

breakup with Eastwood and an undisclosed settlement with him and Warner Bros.,

Sondra Locke did write a tell-all with the Leone-ian title The Good, the Bad,

and the Very Ugly.)

It's easy to forget that Eastwood

didn't just star with Meryl Streep in The Bridges of Madison County, he was her

director, too, and the result is one of the best love stories, middle age be

damned, ever to grace a movie screen. In adapting the purple-prose novel of

thwarted passion between a rural housewife and a photojournalist, Eastwood gave

Streep a gift that wasn't just generous but smart—he reversed the perspective. "The book told the story from the man's

point of view," he says, "but

it's the woman's dilemma of having a family and facing big decisions." Streep

describes a scene in which the lovers fight and she accuses him of standing

apart from life, just being an observer, and says she's just a byway for him. "And he breaks," she says. "He shocked me when it happened. It was

something Sean Penn would be very proud of—you can just march right up to the

podium with that performance. And he cut it out. It wasn't about him. It was a

matter of never losing focus on the piece and its integrity." As for

the notion that a lot of directors don't have a deep interest in women, just

saying that to Streep inspires a vigorous hoot. "That is the understatement of the century," she says. "And that's right, it's just interest.

Clint at some point became interested."

Eastwood has a witty way with

love scenes, particularly the hesitation waltz between people who are just

starting to realize what's happening. De France describes a scene in Hereafter

in which she and Damon are meeting in a public place. "The camera went around and around, circling us. Suddenly Eastwood

says, `Okay, can you kiss the girl?' ”She laughs, adding, "It was not written in the

script!" No, but it's there on the screen, two people surprised by

love, looking utterly real.

In such unlikely films as the

militaristic Heartbreak Ridge, with its gnarled gunnery sergeant (played by our

guy) who has a secret stash of women's magazines he pores over to understand

us—particularly his ex-wife—better, Eastwood has a way of acknowledging the

importance of women. And in Bird, he tells the story of the heroin-doomed jazz

genius Charlie Parker from the perspective of Parker's wife, Chan, with Diane

Venora both a pungent presence and a satisfying reality check throughout the

movie. But never has Eastwood injected a female perspective into a male genre

to greater effect than in Unforgiven, the movie he calls his last western

because he doesn't believe he'll ever find a better one. Unforgiven, which

brought Eastwood his first pair of Oscars in 1993, and the less celebrated 1984

New Orleans noir Tightrope, are two brilliant repudiations of the ethos that

made Harry Callahan and the homeless man on horseback into romantic figures.

Unforgiven opens with a

particularly ugly act of violence: A cowboy cuts up the face of a young

prostitute he thinks has laughed at his small penis. When the bully who runs

the town refuses to punish the cowboy, the prostitutes' enraged madam rallies

them to raise a bounty: "Just

because we let them smelly fools ride us like horses doesn't mean they can

brand us like horses. Maybe we ain't nothing but whores, but we, by God, ain't

horses." That's what brings Eastwood's retired and bitterly regretful

gunslinger—now an impoverished widower with small children—into the drama,

which plays out violently, and largely among men. But the women's implicit

critique of the codes of masculinity infuses the whole movie, preventing it

from becoming just another righteous thrill ride.

In Tightrope, credited to Richard

Tuggle but much of it directed by Eastwood, he creates the antithesis of the

confidently lethal Dirty Harry. Wes Block is a New Orleans homicide detective

riddled with guilty self-doubt who is the devoted single dad of two daughters.

This murkily handsome movie doesn't pit good and evil against each other so

much as explore the thin line between them. Pursuing a serial killer, Block

finds himself in a moral fun house hall of mirrors; among other things, the

killer makes a specialty of murdering the prostitutes Block has taken to

visiting. But the movie's most radical element, in more ways than one, is the

woman Block finds himself increasingly drawn to. She's the smart, no-nonsense

head of a rape crisis centre who teaches self-defence, and as played by the

masterfully understated Genevieve Bujold, she holds out to Block not just the

possibility of redemption but of simple peace. When I asked Eastwood if she was

in Tuggle's script to begin with, he mentioned other things in the script but

said he couldn't remember. I'm not sure I believe him, but that's okay. To go

in 12 years from High Plains Drifter's portrayal of a woman's punishment by

rape to a romance with the kick-ass head of a rape crisis centre is a hell of a

learning curve.