Clint Eastwood's 'The 15:17 to Paris' never feels entirely

real by Owen Gleiberman, Variety February 7, 2018

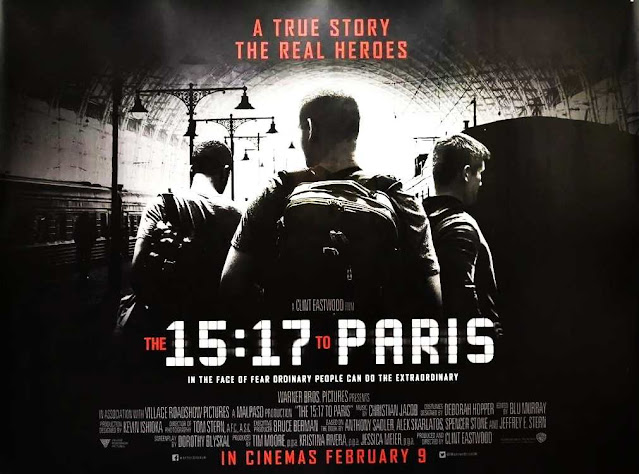

Below: The UK Quad Poster

Clint Eastwood’s “The 15:17 to Paris” is a fluky experiment

of a true-life thriller that sounds, at least on paper, like a metabolic piece

of Eastwood red meat. On August 21, 2015, a man named Ayoub El-Khazzani, armed

with an AK-47, a pistol, and a box cutter, opened fire on the passengers

traveling aboard a high-speed railway train from Amsterdam to Paris. The gunman

was probably an Islamic terrorist (though that has never been determined; he

claimed to be a burglar), and once his assault rifle jammed, he was overcome by

a trio of young American passengers, two of whom were enlisted men: Spencer

Stone, a 23-year-old Airman First Class; Alek Skarlatos, a 22-year-old Army

National Guard Specialist, on leave from his deployment in Afghanistan; and

their long-time buddy Anthony Sadler, a 23-year-old senior at California State

University.

Eastwood re-enacts the incident, shooting it in a

conventionally forceful and exciting hair-trigger hand-held moment-of-truth

style, breaking it into dramatic pieces and circling back to it throughout the

film. He also dramatizes the three young men’s lives leading up to the

incident. He goes back to their delinquent boyhood in Sacramento, and then

follows them through military training and, finally, the impromptu vacation in

Europe that led the three of them — by chance? Or was it fate to board that train?

The highly unusual premise of “The 15:17 to Paris” is that

Stone, Skarlatos, and Sadler all portray themselves. None are professional

actors, but they’re heroes playing heroes, and that means that they’ve got a

bit of inside expertise. It also means — theoretically — that the movie will

bring the bravery of their actions close to the audience with a rare

existential authenticity: the feeling that this is how it looked, this is how

it felt, and this is how it went down.

The reason that’s very Clint Eastwood, even though you can

imagine filmmakers from Edward Zwick to Richard Linklater coming up with the

same concept, is that Eastwood has always had a unique investment in the gritty

conviction of the men of action he portrays, as both actor and director. Dirty

Harry wasn’t just a scowling cop badass in an underworld thriller; he was a guy

who did what had to be done. (He was, in essence, a political character: a

right-wing urban warrior with an agenda expressed through his Magnum.)

Eastwood’s Western heroes, in films from “The Outlaw Josey Wales” to

“Unforgiven,” scowl at the world with the moral weight of their mission. And in

his more recent work, from the down-in-the-muck, rabble-rousing “American

Sniper” to the high-minded, anti-bureaucratic “Sully,” Eastwood has doffed his

cap to true-life manly men whose split-second willingness to act makes the

difference between courage and doubt, victory and defeat. Eastwood isn’t just

making “action films.” He’s keeping alive the dream of what it means to take

action.

If you go into “The 15:17 to Paris” with no idea that you’re

watching three young men play themselves, re-enacting the moment of their own

valor (and let’s be clear: However much the film is advertised, plenty of

people — probably most — will go in having no idea), you’ll see a docudrama

that looks convincing enough, with three performers who sort of resemble movie

stars (they’re tall and handsome, with a natural-born cock-of-the-walk ‘tude),

but who all seem a bit unsure in their roles, which is a little ironic.

As the movie opens, in 2005, Spencer and Alek are getting

ready to graduate from grade school, and their single moms, played by Judy

Greer and Jenna Fischer, go in to have a conference with the boys’ teacher, who

informs them that both kids have ADD. She tells them in such a brusque didactic

manner (“If you don’t medicate them now, they’ll just self-medicate later!”) that

you’re already wishing the movie would stop, reset, and begin with a better

screenplay. (This one is by Dorothy Blyskal; it’s her first.) Going forward,

not every scene is as in-your-face awkward, but there’s a stiff-jointedness to

the repartee, and that’s the last kind of script these novice actors needed.

Eastwood would have been wise to let them improvise — to draw on their

personalities more, revealing things a conventional movie wouldn’t. Instead,

they’re playing cut-and-dried versions of their own selves.

Let’s assume, though, that you go in knowing what the deal

is. It doesn’t take long to grow accustomed to Stone, Skarlatos, and Sadler’s

casual semi-non-acting, because they’re appealing dudes, quick and smart and

easy on the eyes. The oddity of the movie — and this is baked into the way

Eastwood conceived it, sticking to the facts and not over-hyping anything — is

that this vision of real-life heroism is so much less charged than the

Hollywood version might be that it often feels as if a dramatic spark plug is

missing. I’ve long argued for authenticity in movies (especially when they’re

based on true stories), but “The 15:17 to Paris” presents a kind of

walking-selfie imitation of authenticity. The movie creates its own version of

the uncanny valley.

Spencer Stone is the central character. He’s the one who

leads the charge on the train and gets the lion’s share of screen time leading

up to it. Yet to our surprise, he’s the protagonist as genial borderline

screw-up. The childhood scenes, in which the three boys bond over war games,

basketball, and daily trips to the principal’s office of their Christian high

school, are functional in an Afterschool Special way, but then we find Spencer,

after graduation, as a doughy slacker working at a Jamba Juice. A customer

inspires him to join the Air Force, and there’s a training montage in which he

loses the pot belly and seems to find a purpose. Yet he finds neither fulfilment

nor success.

Stone, big and pale, slightly gawky in his crewcut, comes

off as a good guy who’s still something of an overgrown kid, and he reminds you

of certain actors. He’s like the young Woody Harrelson, or a more genial

Michael Rappaport. But there are not a lot of layers to what he shows us. He

goes through the motions of trying out for (and failing) several military

positions, until he seems to find his calling in a wrestling match. But it’s

all served up with too much this-happened-and-then-this-happened neutrality for

us to have a lot of reaction to.

Anthony Sadler, Spencer’s good buddy, is the most

charismatic of the three — he acts with a sly smile that suggests that he, at

least, has things on his mind apart from what’s happening at any given moment.

Alek Skarlatos is the one we feel we know least. He looks like a male model, and

is smiley to a fault, but he always seems like a sidekick. After Spencer’s

military adventures, and a pit stop in Afghanistan (Sadler doesn’t get as much

backstory, the unfortunate implication being that the fact that he’s not a

military man means he doesn’t merit it), the movie unites the three old friends

for a backpacking tour of Europe. Once again, there’s no overhyping of

adventure. Stone and Sadler arrive in Venice wearing their bro ignorance on

their sleeves. In Amsterdam, the three have a wild time on the Euro disco

floor, but in the end it’s a chaste evening. And then they head to Paris.

Spencer has already regaled with Sadler with a speech about

how he feels his life building toward something. It’s a pinch of fortune-cookie

mysticism sprinkled over what was basically a random horrific event. But aboard

that train, there’s nothing random about how Spencer Stone takes charge: Once

the killer (played by Ray Corasani) starts rampaging through the cars, Spencer

acts with shocking selflessness and courage; if that assault rifle hadn’t

jammed, he’d be dead. His wrestling training comes in handy, and the other two

men assist with punches and rifle-butt bashes to the face. Spencer also draws

on his paramedic training to save the life of a passenger who gets shot through

the neck.

It’s all startlingly matter-of-fact. For a few minutes, the

film rivets our attention. Yet I can’t say that it’s transporting, or highly

moving, or — given the casting — revelatory. There’s an obvious precursor to

“The 15:17 to Paris,” and that’s “United 93,” which I have never hesitated to

call the one great post-9/11 drama. It, too, stayed as true as possible to the

most minute facts — and it also featured a number of non-actors (albeit in

small roles, in the control tower) who’d actually lived through what they were

depicting. Yet the brilliance of “United 93” is that its director, Paul

Greengrass, took what happened that day — even from the point of view of the

terrorists — and made each action feel joined to every other action. He created

a unified-field thriller. Eastwood, in “The 15:17 to Paris,” does the opposite.

The film keeps telling us that what happened aboard that train was the fulfilment

of something, but neither the event nor the three actors re-enacting it seem

completely real. They seem like pieces of reality trapped in a movie.

Clint

Eastwood derails a tale of real-life terror

Peter

Bradshaw's film of the week, The Guardian, Thursday 8 Feb 2018

Three young Americans who bravely

foiled an attack on a train play themselves in a drama that focuses too much on

their excruciatingly dull backstories.

The authentic courage of three

American heroes who foiled a terrorist attack has been anti-alchemised by Clint

Eastwood into a strangely boring, dramatically inert film in which the main

characters remain as opaque and unreadable as sphinxes to the very last.

But there is some interest in

this film nonetheless because of the experimental chutzpah Eastwood has showed

in using – not Chris Hemsworth, not Bradley Cooper, not Trevante Rhodes – but

the three actual guys stolidly playing themselves. (The attacker, one Ayoub

El-Khazzani, being now incarcerated, was not available for filming.) The

resulting film looks bizarrely like an essay in take-it-or-leave-it social

realist grit or radical, non-professional clunkiness, as if before filming Clint

watched Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake and Tommy Wiseau’s The Room and couldn’t decide

which one he liked more.

The men themselves were Spencer

Stone, Alek Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler; two were from the US military,

trained in combat and first aid, and at least one had a strong Christian faith.

While backpacking in 2015 the three tackled a heavily armed jihadi terrorist on

a train from Amsterdam to Paris – saving dozens of lives. There also happened

to be a British guy there whose contribution, following the tradition of

Hollywood war movies, has been pretty much cheerfully ignored.

The effect of realness in this

film is a strange one. The three are bad at acting, of course, but not as bad

as all that, and a basic level of woodenness is important for underscoring the

film’s genuine quality, because how disconcerting would it be if they all

turned out to be talented thespians, a trio of Benedict Cumberbatches? The

movie starts with the tense initial situation aboard the train and then –

exasperatingly – keeps cutting back to the three men’s dull and diffidently

directed backstories, their unhappy and unsatisfactory childhoods, their early

lives in the forces, and then their quite excruciatingly boring backpacking

holiday, which we all have to live through in real time before they climb

aboard the 15:17 to Paris and we reach the main event.

Except that, weirdly, the attack

is not the main event. That comes one step later when Eastwood, with almost

avant garde cheek, uses actual footage of French President François Hollande

presenting the three men with the Légion d’honneur and we seamlessly cut away

to the actors playing their adoring mothers and relatives. Even here, though,

he can’t resist slathering syrupy music on the soundtrack to make sure we

realise that it’s an emotional moment.

The attack itself is robustly and

forthrightly shot, without the nerve-twisting horror of Paul Greengrass’s 9/11

movie United 93, it is true, but that was a different situation. It is all over

pretty quickly. It seems almost anticlimactic and detached. Perhaps that is

faithful to the experience itself.

But, intentionally or not, the

real meat of the film is that mind-bendingly boring holiday: endless beers,

endless coffees, endless selfies. No tension between the guys. No real

connection either. They look as if they don’t know each other all that well.

But then again, that is probably what real friends actually look like, without

artificially scripted filmic moments to denote friendship. Eastwood and his

screenwriter Dorothy Blyskal, who has adapted the three men’s book about the

event, have rigorously avoided any premonitions or creepy omens, although

Spencer talks about God having a purpose to his life. No, we just trudge

through the vacation, like being forced to look at someone else’s photos.

It is dull. But perhaps that’s

what life is – dull. Especially compared to a sudden burst of frenetic, heroic

activity on a train when you’re faced with a theocratic murderer and your

training kicks in.

As for Stone, Skarlatos and

Sadler, my admiration for them knows no bounds. But their real presence in the

film? It reminded of the Player in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

Are Dead who said he once hanged someone for real on stage and a baffled

audience just took it for bad acting. A documentary by Eastwood might have

served everyone better. But François Hollande might be in line for a special

reality Oscar for that climactic movie speech he didn’t realise he was giving.

The 15:17 to Paris, www.rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz, February 8, 2018

On August 21, 2015, three

Americans traveling through Europe subdued a terrorist who tried to kill

passengers on the Thalys train #9364 bound for Paris. The men were Airman First

Class Spencer Stone, Oregon National Guardsman Alek Skarlatos, and college

student Anthony Sadler. They'd been friends since childhood. The gunman, a

Morrocan named Ayoub El Khazzani, exited a washroom strapped with weapons,

wrestled with a couple of would-be heroes, and shot one of them in the neck

with a pistol. Stone tackled Khazzani and locked him in a choke hold while

being repeatedly sliced with a knife. Stone's two friends plus Chris Norman, a

62-year-old British businessman living in France, hit Khazzani with their fists

and with the butts of firearms that he'd dropped into the struggle until he

finally lost consciousness. Then they kept the shooting victim alive until the

train was able to stop and let police and emergency medical technicians

onboard. For their bravery, Norman, Sadler, Skarlatos, and Stone were made

Knights of the Legion of Honour by French president François Hollande, and

given awards, parades, and talk show appearances back home.

As Hollywood film fodder, this

is—or should have been—a slam dunk, even for a director who insisted on having

the three Americans play themselves, which is the case here. To call Clint

Eastwood's "The 15:17 to Paris" a mixed bag would be generous. It

packs all the wild action you came to see into a 20-minute stretch near the

end, and elsewhere gives us something like a platonic buddy version of Richard

Linklater's "Before" trilogy. This is an audacious choice regardless

of whether you're into it.

Too bad seeing this trio re-enact

their European vacation is as absorbing as watching a friend's video footage of

a trip you didn't go on. As cinematographer Tom Stern's camera hangs

close-but-not-too-close, Sadler, Stone and Skarlatos retrace their steps,

traveling from Rome and Venice to Berlin and Amsterdam, cracking jokes about

old buildings and sculptures, flirting with attractive women, getting liquored

up in a nightclub. You feel like you're right there alongside them. This is an

eerie and astonishing feeling when they're re-enacting the train incident, but

not when they're ordering food or taking selfies.

There's a long tradition of real

people starring in films about their lives, from Pancho Villa and Jackie

Robinson to Muhammad Ali and Howard Stern, and some film cultures, particularly

Italy's Neorealism and Iran's post-1980s docudramas, have a proud history of

extraordinary nonprofessional performances. World War II Medal of Honor winner

Audie Murphy went straight into acting with help from a famous admirer, James

Cagney, played himself in 1955's "To Hell and Back," based on his

same-titled memoir, and died 21 years later with 50 screen credits. There

haven't been too many instances where audiences looked at these performances

and thought, "Wow, what an incredible actor—a professional wouldn't have

added anything." But if the nonprofessional seems relatively comfortable

onscreen and lets a bit of personality come through, the film can work. And the

performance might be likable. Or at least not painful.

I'm relieved to report that not

only are these three less than terrible in their big screen debuts, they're

kind of charming, once you decide to make peace with the fact that Eastwood has

traded the depth and nuance that a professional can bring for the unpredictable

freshness you can only get from casting newcomers. Stone is an unexpectedly

striking screen presence: a towering, broad-shouldered, lethal goofball with a

comic book henchman's jawline and a bubbly, impatient manner of speaking. There

are moments when his rat-a-tat delivery, practically tripping over his own

words, suggests an unholy fusion of Drew Carey and young Gary Busey. I wouldn't

be surprised to see him wind up on a sitcom opposite Tim Allen or Kevin James.

The other two seem to have been granted screen time in proportion to their not-terribleness.

We get a lot of Stone with Sadler, who's not a particularly deep actor, to put

it mildly, but is disarmingly natural and has a great rapport with his pal.

Skarlatos, a handsome but wooden nice guy, is kept mostly offscreen until he

joins the others.

But no matter what you think of

these men as thespians, their performances are the least of the film's

problems. A good 70% of "The 15:17 to Paris" is inert, its affable

nothingness redeemed only by the laid-back charisma of three men who once again

find themselves in extraordinary circumstances and have no choice but to rise

to the occasion.

The film starts with a flashback

to the trio's childhood, with Jenna Fischer and Judy Greer as Skarlatos and

Stone's mothers, that promises an American Fighting Man Epic in the vein of

"Sergeant York" or "Hacksaw Ridge." But these scenes fall

almost entirely flat, with character traits being more described than

dramatized. The scene where the moms argue with a snotty administrator who

tries to diagnose Stone with ADHD while dissing both women for being single

mothers might be the worst five minutes Eastwood has put onscreen, but it has

lots of competition here. How Eastwood managed to get worse performances out of

the professional actors playing the young heroes than the adults who'd never

acted is a mystery that only another director can properly unravel. Ace

character actors Tony Hale and Thomas Lennon are wasted as, respectively, the

school's principal and gym coach. Jaleel White is given just one scene to

convince us that he's a great teacher who inspired the boys' interest in

history; it lasts about 60 seconds and ends with him handing them a manila

folder full of maps. The moms mention God occasionally, but usually in a stilted

way, and their families' spiritual lives aren't examined in any detail (though

there are a couple of prayers in the film, which is rare for a Hollywood

movie).

The screenplay, adapted by

Dorothy Blyskal from a book co-written by the trio plus Jeffrey E. Stern, is

often painfully awkward and obvious. Earnest discussions of fate and destiny

are shoehorned into shallow but generally likeable (and seemingly improvised)

scenes of the guys talking to each other, and to people they meet during their

journey. A couple of the latter are so odd that they verge on sublime, like the

bit when an old man at a bar talks them into going to Amsterdam by recounting

the illicit good time he just had there.

But for the most part, "The

15:17 to Paris" is a study in misplaced priorities. While the re-enactment

of the incident on the train is superb—Eastwood has always had a flair for

staging unfussy yet shockingly brutal screen violence—I'd have happily traded

the lead-up hour of marshmallow fluffery for scenes that showed what happened

to the guys once they got back to their home country and were treated like gods

on earth (though, in fairness, Eastwood might've figured he told that story

already in “Flags of Our Fathers”). And there are some groaner choices, like

Eastwood's refusal to age Fischer and Greer for their scenes opposite their

now-grownup sons, which makes it seem as if they had them when they were 12;

the near-omission of Sadler's parents from the narrative, which inadvertently

turns a co-equal lead character into The Black Friend; and the way Eastwood

keeps the terrorist literally faceless during his first few flashback

appearances, by focusing on his hands, his feet, his knapsack and wheeled

suitcase, and the back of his neck.

I've read that Eastwood asked the

French government if he could get Khazzani to play himself, too, but was

refused. Is this why he portrayed him as a non-person—just another Bad Thing

happening to Good People?

I wanted to know how Khazzani ended up on that train

as well—not because he deserves any sympathy (he doesn't) but because his is

also a tale of social conditioning and sheer willpower, and might have

reflected off the main trio's story in

illuminating ways. For an example of how to do this in a thoughtful,

responsible manner, see Anurag Kashyap's 2007 film "Black Friday,"

which retold the same bombing from the point-of-view of the terrorists and the

police, in two different halves. Eastwood did something similar with

"Flags of Our Fathers" and "Letters from Iwo Jima." But for

the most part, he has become increasingly uninterested in that kind of

complexity, despite having devoted the first 20-plus years of his directing

career to letting us see the evil in good people, and the good in the evil.

While there's something innately

inspiring about Eastwood continuing to crank out films 48 years into his

directing career, there's a downside: his batting average has never been

terrific, and his game has slipped a lot since the Iwo Jima films. There are

intriguing aspects to nearly all of his films, but he's only made maybe six or

seven that are excellent from start to finish—even the mostly good ones have

bad scenes and sections—and in the last 20 years, even his good work has

included a lot of ill-considered, amateurish, or flat-out baffling elements,

like the screechingly caricatured parents in "Million Dollar Baby,"

and Chris Kyle doting on an obviously fake infant in "American

Sniper." Eastwood is famous for working fast and bringing his movies in on

time and under budget, and "The 15:17 to Paris" is another example of

that legendary efficiency: supposedly he decided to tell the trio's story after

giving them a Spike TV Guys' Choice Award just 19 months ago. But breeziness is

not, in itself, an unassailable virtue. There hasn't been a single Eastwood

film since "Unforgiven" that couldn't have benefited from script

rewrites, plus a few trusted advisors with the nerve to tell him that a

particular choice was ill-advised. (I know, I know—who wants to tell Clint

Eastwood he's wrong? Nobody who's seen him use a hickory stick in "Pale

Rider," for starters.)

The movie's greatest virtue,

which might be enough to make it a critic-proof hit no matter what, is its

poker faced sincerity. This extends to faithfully reproducing a Red State

worldview that was also showcased in "American Sniper" and

"Sully." A lot of U.S. moviegoers are going to feel seen by this

film, and that's a net gain for American cinema, which is supposed to be a

populist art form representing the body politic as it is, not merely as the

industry wishes it could be. If only someone could've heroically intervened to

save this movie.

Clint Eastwood's dramatic re-creation stalls at the station by

Michael Phillips, Chicago Tribune, February 8th 2018

An oddly misguided act of generosity, director Clint

Eastwood’s “The 15:17 to Paris” may be the first film from Eastwood that lacks

a storytelling compass and a baseline sense of direction.

The docudrama follows a screenplay by first-timer Dorothy

Blyskal, taken in turn from the nonfiction account (written with Jeffrey E.

Stern) by the three young Americans, friends since childhood, who thwarted a

2015 terrorist attack on an Amsterdam train bound for Paris.

Their story, and Eastwood’s 36th film behind the camera,

builds on the foundation of their quick, decisive, successful act of courage.

They saved lives and did a great deal to bolster the image of Americans abroad,

at a time when films such as Eastwood’s own “American Sniper” exported a

divisive but extraordinarily profitable image of another, steelier kind.

So why does the movie come to so little?

Facts first. In 2015, Spencer Stone was an Air Force airman.

He and Anthony Sadler, an old pal from Sacramento, Calif., studying for a

degree in kinesiology, met up in Amsterdam with Alek Skarlatos, an Oregon

National Guard specialist back from a tour in Afghanistan.

On board a train to Paris, they encountered a lone

terrorist, Ayoub El Khazzani, an apparent ISIS loyalist armed with an assault rifle,

among other weapons, and 300 rounds of ammunition. We see fragments of the

run-up to the aborted attack at the film’s start and, here and there,

throughout “The 15:17 to Paris.” Dutifully, and photographed for maximum

audience satisfaction at seeing the bad guy get his, Eastwood saves the

sequence in full for its proper place in the climax.

Just three weeks before filming commenced, Eastwood decided

to cast the real men as themselves, with various, smaller real-life survivors

and bystanders as themselves. They’re surrounded and supported by well-known

actors, as well as by unknowns playing the Christian middle-school-age Stone,

Sadler and Skarlatos. Judy Greer and Jenna Fischer, doing all they can with

barely characterized roles, portray the mothers of Stone and Skarlatos,

respectively. In their very different skill sets, these actresses seek the same

results as their non-actor colleagues: as much simplicity and honesty as

possible. At its best, that’s Eastwood’s style.

But he’s working with a script that barely functions. The

film wobbles between flashbacks and flash-forwards, and has no interest in

giving us a sense of what they guys were, and are, really like, or how they

click together as friends. It can't be easy to play yourself in a movie. The

performances this movie rests on feel tentative, hesitant, slightly sheepish.

The script doesn’t help. Far too much of “15:17 to Paris” is

taken up with travelogue scenes of the young men touring Venice, or Rome, or

hitting the dance floor in Amsterdam. Eastwood lingers over one drab expository

or atmospheric nothing after another (“Wow, look at that view!”; “We gotta get

some gelato”). The key foreshadowing, played up in the trailers, arrives when a

reflective Stone says: “Ever feel like life is just pushing us toward

something, some greater purpose?” That’s a key moment, and he really did say

it. Yet on screen, it comes off as ginned-up and more than a little canned.

Many will disagree, and already have. This is hardly the

first American movie to cast a true-life dramatic reconstruction with the real

people as themselves: To varying degrees of success, we’ve had everything from

Audie Murphy in “To Hell and Back” to Howard Stern in “Private Parts.” But when

Eastwood’s film is over, you may think back to an earlier Eastwood film, “Flags

of Our Fathers.” That multi-strand WWII picture dealt in part with the way

real-life heroics become fodder for publicity, and how the complicated feelings

of the men involved take a back seat to the larger cause. It’s the last thing

he wanted, I’m sure, but Eastwood’s latest ends up feeling like a stunt.

We love stories of real-life heroics and grace under lethal

pressure. But we need them to be more than the sum of their stirring

intentions.

In ‘The 15:17 to Paris,’ Real Heroes Portray Their Heroism, by

A.O. Scottfeb. The New York Times, February 7th, 2018

On Aug. 21, 2015, Ayoub El Khazzani boarded a high-speed

train en route to Paris, armed with a knife, a pistol, an assault rifle and

nearly 300 rounds of ammunition. His attack, apparently inspired by ISIS, was

thwarted by the bravery and quick thinking of several passengers, notably three

young American tourists: Alek Skarlatos, Anthony Sadler and Spencer Stone.

Their heroism is at the center of Clint Eastwood’s new

movie, “The 15:17 to Paris,” a dramatic reconstruction as unassuming and

effective as the action it depicts. Based on a book written (along with Jeffrey

E. Stern) by Mr. Sadler, Mr. Skarlatos and Mr. Stone, the film stars them, too.

The practice of casting nonprofessionals in stories that

closely mirror their own experiences has a long history — it’s a staple of

Italian neorealism, the films of Robert Bresson and the Iranian cinema of the

1990s — but it remains a rarity in Hollywood. Usually the most we can expect is

a poignant end-credits glimpse of the real people our favorite movie stars have

pretended to be for the previous two hours. After all, part of the appeal of

movies “inspired by true events” is the chance to admire the artistry of actors

(like Tom Hanks’s, say, in Mr. Eastwood’s “Sully”) as they communicate the grit

and gumption of ordinary Americans in tough circumstances.

But the thing to admire about “The 15:17 to Paris” is

precisely its artlessness. Mr. Eastwood, who has long favored a lean,

functional directing style, practices an economy here that makes some of his

earlier movies look positively baroque. He almost seems to be testing the

limits of minimalism, seeing how much artifice he can strip away and still

achieve some kind of dramatic impact. There is not a lot of suspense, and not

much psychological exploration, either. A certain blunt power is guaranteed by

the facts of the story, and Mr. Eastwood doesn’t obviously try for anything

more than that. But his workmanlike absorption in the task at hand is precisely

what makes this movie fascinating as well as moving. Its radical plainness is

tinged with mystery.

Who exactly are these guys? They first met as boys in

Sacramento, which is where we meet them, played by Cole Eichenberger (Spencer

Stone), Paul-Mikel Williams (Anthony Sadler) and Bryce Gheisar (Alek

Skarlatos). Alek and Spencer, whose mothers (Judy Greer and Jenna Fischer) are

friends, pull their sons out of public school and enroll them in a Christian

academy, where they meet Anthony, a regular visitor to the principal’s office.

Frustrated by the educational demands of both church and

state, the boys indulge in minor acts of rebellion: toilet-papering a

neighbor’s house, swearing in gym class, playing war in the woods. They are

separated when Alek moves to Oregon to live with his father and Anthony changes

schools, but the three stay in touch as Anthony attends college and Alek and

Spencer enlist in the military. Spencer, stationed in Portugal, meets up with

Anthony in Rome, and Alek, who is serving in Afghanistan, visits a girlfriend

in Germany before joining his pals in Berlin. They go clubbing in Amsterdam,

wake up hung over and, after some debate, head for Paris.

To call what happens before the confrontation with the

gunman a plot, in the conventional sense, does not seem quite accurate. Nor do

Spencer, Anthony and Alek seem quite like movie characters. But they aren’t

documentary subjects, either. Mr. Eastwood, famous for avoiding extensive

rehearsals and retakes, doesn’t demand too much acting. Throughout the film,

the principal performers behave with the mix of affability and reserve they

might display when meeting a group of people for the first time. They are

polite, direct and unfailingly good-natured, even when a given scene might call

for more emotional intensity. In a normal movie, they would be extras.

And on a normal day, they would have been — part of the mass

of tourists, commuters and other travelers taking a quick ride from one

European capital to another. At times, Spencer, the most restless of the three

and the one whose life choices receive the most attention, talks about the

feeling of being “catapulted” toward some obscure destiny. But “The 15:17 to

Paris” isn’t a meditation on fate any more than it is an exploration of the

politics of global terrorism. Rather, it is concerned with locating the precise

boundary between the banal and the extraordinary, between routine and violence,

between complacency and courage.

The personalities of the main characters remain opaque,

their inner lives the subject of speculation. You can wonder about the sorrow

in Alek’s eyes, about the hint of a temper underneath Spencer’s jovial energy,

about Anthony’s skeptical detachment. But at the end of the movie, you don’t

really know them all that well. (You barely know Chris, a British passenger who

helped subdue Mr. Khazzani, at all. He is seen but not named.)

Producing the illusion of intimacy is not among Mr.

Eastwood’s priorities. He has always been a natural existentialist, devoted to

the idea that meaning and character emerge through action. At the end of “The

15:17 to Paris,” a speech by former President François Hollande of France

provides a touch of eloquence and a welcome flood of feeling. But the mood of

the film is better captured by Mr. Skarlatos’s account of it, published in news

reports after the attack: “We chose to fight and got lucky and didn’t die.”

'The 15:17 to Paris' turns a headline grabbing true story

into a lackluster Hollywood movie, By Kenneth Turan, The Los Angeles Times,

February 8th, 2018

In 1921, Louis Sonney, having single-handedly captured

bandit Roy Gardner, "the most hunted man in Pacific Coast history," played

himself in a film called "Crime Doesn't Pay" and toured the nation

with it on the Pantages vaudeville circuit.

In 1955, Congressional Medal of Honor winner Audie Murphy,

America's most decorated World War II soldier, played himself in a Technicolor and

Cinemascope version of his wartime exploits, "To Hell and Back,"

which became a major hit.

Now, in 2018, Anthony Sadler, Alek Skarlatos and Spencer

Stone play themselves in director Clint Eastwood's "The 15:17 to

Paris," the once-again true story of how a trio of friends disarmed a

heavily armed terrorist intent on killing as many as possible of the 500-plus

passengers on a train speeding to Paris from Brussels.

As a democratic culture, Americans are understandably

attracted to the notion of everyday heroes, of brave warriors hidden in plain

sight, people ordinary on the surface but possessed of astonishing reserves of

courage that reveal themselves when emergency calls.

Eastwood dealt with a similar situation in 2016's

"Sully," starring Tom Hanks as the intrepid real-life commercial

airline pilot who made a successful emergency landing on the Hudson River in

the dead of winter, so he understands that these stories demand the

just-the-facts style of direction he's so good at providing.

But though the sequences of the actual heroism on the

Paris-bound train are fully as crisp and involving as you'd expect, the other

sections of the film, intent on demonstrating how undeniably everyday the three

participants were up to that crucial moment, fall regrettably flat.

All indications to the contrary, despite the attempts of

first-time screenwriter Dorothy Blyskal (working from a book Sadler, Skarlatos

and Stone wrote with Jeffrey E. Stern), there does not appear to be an

involving feature film in their story, undeniably heroic though it is.

The nearly 50 movies Murphy went on to make after "To

Hell and Back," notwithstanding, Eastwood took a risk in casting the real

protagonists in their own story.

Though none of the trio should give up their day jobs just

yet, it's not their lack of compelling charisma that is the picture's main

problem, but rather that the on-screen story has not come up with anything

compelling for them to do outside those few life-and-death minutes on the

train.

The film teases that attack from its opening frames of an

ominous looking man walking through the Brussels train station on the way to

boarding the 15:17, but soon flashes back to one of its major focuses, a bland

after-school special-style examination of the bond the men forged as

middle-school students in Sacramento circa 2005.

No one, to put it mildly, sees these kids as potential

heroes. Rambunctious but good-hearted, young Spencer (William Jennings) and

Alek (Bryce Gheisar) get sent to the principal's office a lot, much to despair

of their struggling single parent mothers, played by Judy Greer and Jenna

Fischer, who nevertheless have their backs.

At that office is where the boys meet young Anthony

(Paul-Mikél Williams), also a frequent subject of Christian school discipline.

The three become fast friends, sharing an interest in war and weaponry and

listening intently when a teacher, in one of the movie's numerous bits of foreshadowing,

talks of Franklin D. Roosevelt as someone who "did the right thing at the

right time to defuse critical situations."

As adults, the three go their separate ways and lead what

appear to be haphazard lives. Sadler enrolls at Cal State Sacramento and is not

heard from a lot, while Skarlatos is deployed by the Oregon National Guard to

what looks like a nondescript tour in Afghanistan.

Stone, seen reciting the Prayer of St. Francis, has a strong

sense of mission. That takes him to the Air Force, but he has a lot of false

starts there, which we see in uninvolving detail. Still, he continues to

stubbornly believe "life is just pushing us toward something, some greater

purpose."

The friends decide to reunite on a European vacation, but

before we get to the train trip that made them famous, we are shown a detailed

rundown of all the standard sights they took in — including the Trevi Fountain

and the Colosseum in Rome, the bars of Amsterdam, the canals of Venice, the

city's iconic Piazza San Marco and pricey Gritti Palace restaurant, to name

just a few.

While it is nice to have the regular-guydom of these men

highlighted, this marking-time itinerary tests the limit of how much the buying

of gelato and the taking of multiple selfies can involve us.

As noted, the disarming of the terrifying El Khazzani is

well presented in a "You Are There" way and gives us a real sense of

the kind of bravery involved. A single act of heroism can truly transform a

life, but that action does not necessarily make for a transformative motion

picture.

Eastwood on track with The 15:17 to Paris, by Alan Corr,

RTE, Friday, 9th February, 2018

Clint Eastwood's latest is a naturalistic, no frills

retelling of real life events which sees real life heroes playing themselves

There is something of Paul Greengrass’s United 93 in this

compact and faithful retelling of the dramatic events on board an intercity

train from Amsterdam to Paris in August 2015 when three young American men

foiled a terrorist attack on 500 passengers. However, unlike Greengrass's

unbearably tense 9/11 drama, the outcome here is a far happier one.

Clint Eastwood has taken the brave and novel approach of

casting the three heroes - Spencer Stone, Anthony Sadler and Alek Skarlatos -

as themselves and it really pays off in what is a naturalistic real life story.

After the bravado Sully starring Tom Hanks, this tale of derring do seems the

obvious choice for Eastwood.

The veteran director scrolls back through the three

childhood friends’ upbringing - troublesome years in a faith school, a

childhood fascination with the military - to give the full story of how one act

came to define them all. However, by the time the boys decide to undertake that

American custom of a backpacking trip around Europe we may be running out of

story.

The imminently likeable and gentlemanly Stone is the leader

here and he has real screen presence as the recent army recruit who feels a

divine force coursing through him and who avers several times in the film's

short running time that life is somehow pushing him towards some great act. At

one point he murmurs without a trace of irony, "I just wanted to go to war

and save lives."

Eastwood weaves themes of faith, fate, and friendship and

while it has some of his usual gung-ho worship of the military (he’s as at home

in boot camp as he was in Heartbreak Ridge), nobody could begrudge his salute

to these real life heroes.

However, he is not beyond sending flag and country up. When

the three Californian amigos take a tour of Berlin and stand at the site of

Hitler’s bunker, they are taken aback to hear that he perished just feet below

them as the Russians closed in. "You Americans can’t take the credit every

time evil is defeated," their guide laughs.

When it arrives, the crucial train scene is handled with

Eastwood’s flair for directing action and violence. Given the deadly serious

events it portrays, this is an easy-going, feel good watch. Just like the train

they are about to board, these three men are all hurtling toward an incredible

date with destiny.

'The 15:17 to Paris' review: heroes' journey stalled by

dullness, by Ethan Sacks, NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, Thursday, February 8th, 2018

Call it a cinema veri-test.

By casting the actual American heroes who foiled a terrorist

attack to play themselves in “The 15:17 to Paris,” director Clint Eastwood

tapped into an unprecedented level of realism for a drama.

The three childhood friends — former U.S. Airforce Airman

First Class Spencer Stone, National Guardsman Alek Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler

— certainly deserve to be celebrated like movie stars for the bravery and

selflessness they exhibited when their European vacation was interrupted in

horrific fashion on Aug. 21, 2015.

That’s when Stone was injured tackling and disarming an

assault rifle-toting gunman before he could open fire on the terrified

passengers. And if that wasn’t dramatic enough, Stone ignored his own slash

wounds to administer life-saving medical aid to the lone passenger who was

shot. The climax of “The 15:17 to Paris” recreates the event in hyper-realistic

detail with the very people involved. Eastwood even got the gunshot victim who

nearly died, Mark Moogalian, to play himself.

The sequence is among the most exciting moments captured on

screen in recent memory. But that still leaves the vast majority of the film’s

94-minute run time to fill. And most of it sure feels like padding.

Screenwriter Dorothy Blyskal takes the story all the way

back to when the trio first met as middle school students, through their

respective starts in the military and into the first few stops of their

backpacking travels through Europe. For the most part it’s about as interesting

as watching strangers' home movies.

A sequence showing Skarlatos’ tour of duty in Afghanistan,

for example, involves a lost backpack that is eventually recovered without any

problem. Stone and Sadler meet a woman while touring Venice, they have lunch

together, and then she goes off on her way. Not exactly some of the most

exciting moments captured on screen in recent memory.

The three heroes may now be movie stars, but they’re not yet

actors. They were not helped by heavy-handed dialogue like, “Do you ever feel

like life is pushing us toward something, some greater purpose?”

Eastwood faced similar issues with his last film, “Sully,”

and he still hasn’t figured out how to take a relatively short dramatic event

and build a movie around it. It helped to have Tom Hanks in the cockpit.

This time around it’s all put on the broad shoulders of

Stone, Skarlatos and Sadler. And that’s a lot to ask, even of the type of guys

who fearlessly run toward danger.

The 15:17 To Paris reviews: Critics SLAM Clint Eastwood

movie - ‘Excruciatingly dull’, by Shaun Kitchener, The Express, Thursday

February 8th 2018

THE 15:17 TO PARIS has had very negative reviews from

critics ahead of its release tomorrow. The Clint Eastwood true-story movie,

which stars the real-life heroes it is about, has been called out for being

“dull” and a “right-wing wet dream”.

The film is about three American heroes who helped scupper a

terrorist attack on board a train, with the men playing themselves.

The Guardian gave only two stars, saying the focus on their

backstories is “excruciatingly” boring, and also slammed the “woodenness” of

the central performances.

Radio Times were also unimpressed, giving one star and

saying it “awkwardly pivots from religious fervour to testosterone-fuelled

military recruitment video to backpacking travelogue”

“Eastwood’s hardline Republican politics have been well

documented over the years, and his version of the heroes’ book of the same name

has the air of a right-wing wet dream,” they added.

Rolling Stone were slightly more positive, giving

two-and-a-half stars out of a possible four, but said: “Through no fault of

their own – hey, you try acting without training – these non-pros simply can't

bring the film to vivid life.

“They get scant help from first-time screenwriter Dorothy

Blyskal, who adapts the mens' published account of their experience in The

15:17 to Paris: The True Story of a Terrorist, a Train and Three American Heroes

with a dispiriting flatness.”

The Financial Times gave a two-star noticing, saying:

“Re-read the news story: that was good. Don’t bother with the movie.”

Entertainment Weekly gave a D-grade, saying the film is a

“well-intentioned disaster”.

The movie received a lowly 25% score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Film Review: The 15:17 to Paris, by Daniel Eagan, Film Journal

International, Thursday, February 8th 2108

Three friends help prevent a terrorist attack on a train.

No-frills account from director Clint Eastwood with the real-life heroes as

stars.

When they stopped a terrorist attack onboard a high-speed

train to Paris, Spencer Stone, Alek Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler won acclaim

around the world. A best-selling book followed. When Clint Eastwood decided to

turn the incident into a movie, he took the unusual step of casting the three

friends as themselves.

Like the book, Dorothy Blyskal's screenplay opens up the

story, going back to the trio's childhood in Sacramento, Calif. All three are

troublemakers at school. Spencer underachieves in college before failing at

several Air Force positions. Alek goes from community college to the Oregon

National Guard, ending up in Afghanistan.

Working with his longtime cinematographer Tom Stern,

Eastwood shoots these scenes with customary efficiency, refusing for the most

part to pump up emotions. As a result, The 15:17 to Paris can seem dry at

times, with long stretches devoted to military training or to scenes that have

no obvious payoff.

Eastwood begins the movie with glimpses of Ayoub (Ray

Corasani), the terrorist who brought guns and hundreds of rounds of ammunition

aboard the Paris-bound train. Later the story will occasionally flash forward

from a school scene to an incident on the train. Sometimes the connections are

obvious, like the history teacher who asks his students if they would know what

to do in an emergency.

At other times the shifts feel contrived, an expedient way

to remind viewers that the scenes they are watching will eventually get

somewhere, mean something. Throw in Spencer's obsession with guns and strong

religious beliefs, and The 15:17 could easily be passed off as red meat for

right-wingers.

But look again. Who are these heroes? They are kids who were

bullied, who came from broken homes, poorly educated, not too smart to begin

with. They are the ugly Americans touring Europe, the ones with selfie sticks

and sweatpants, the ones who don't understand the language or the history of

the places they are visiting. They're loud, they drink too much, and they pray.

What the movie points out is that if we want to call them

heroes, this is who they are. If you think what they do and say isn't exciting

enough, this is still the story they lived, the story they wanted to tell.

Eastwood asks us to see beyond our prejudices and embrace lives that seem so

different from ours.

The attack itself, shot aboard a moving train, is a model of

taut, focused filmmaking. Eastwood and editor Blu Murray cut out all the flab,

fashioning a sequence of textbook intensity.

The 15:17 ends with the heroes receiving the Legion of Honor

from French President François Hollande (a combination of real and recreated

footage), then enjoying a parade in Sacramento, Eastwood choosing not to

examine the complications the three subsequently experienced.

As actors, Stone, Skarlatos and Sadler look comfortable and

believable, although without the obvious star power to suggest future film

roles. (Their performances aren't unprecedented—Congressional Medal of Honor

winner Audie Murphy played himself in 1955's To Hell and Back.) What Eastwood

has done, with his customary skill, is show us why we should care about them.

The 15:17 to Paris, by Joshua Rothkopf, Time Out London,

Thursday 8th February, 2018

Director Clint Eastwood bobbles a true tale of heroism,

stranding three men who never should have been asked to re-enact their own

courageous moment.

By one cosmic yardstick, the three American tourists who

foiled a terrorist attack on a 2015 Amsterdam-to-Paris train were in exactly

the right place at the right time: They acted when they had to, wrestling an

armed gunman to the floor and preventing untold carnage. Those same three

Americans don’t act in ‘The 15:17 to Paris’ – they can’t act, because even

though Spencer Stone, Alek Skarlato and Anthony Sadler have been cast as

themselves, they’re not actors. They’re at best beefy twentysomethings with

muscle memory. Dramatically inert and flatter than a buzz cut, the movie ends

up diminishing their moment of heroism by turning it into a defiantly

amateurish piece of junior-high-grade theatrics (the film asks the impossible

of people who have already achieved greatness), as if to say: Reality doesn’t need

to be gussied up. Alas, it does, and saying so doesn’t make you disrespectful.

Anything that could have been done to shift focus away from

these bros – who come across as likeable but blank interlopers in their own

story – should have been considered. Instead, the paint-by-numbers screenplay

by Dorothy Blyskal (mainly a production assistant prior to this job) emphasizes

their deficiencies. It leans heavily on cringe-inducing moments of obviousness,

setting up the boyhood friends as detention-prone loners who prefer playing

wargames in the woods. You get no less than two parent-teacher conferences in

the first 20 minutes alone, both of which end in sassy you-don’t-know-my-son

walkouts. (Jenna Fischer and Judy Greer, as the mothers, try to speed things along.)

Shifting to the adult Stone, Skarlato and Sadler, the movie piles on an hour of

vacation travelogue in Rome, Venice and Amsterdam, during which beers are

quaffed, selfies are taken and European women are ogled (but never disrespected

or even touched). The profanity-free squareness is close to excruciating: you

won’t believe how boring it is partying with real-life heroes.

Say what you will about director Clint Eastwood’s onscreen

rectitude as a gun-toting icon, he’s never been a safe filmmaker. Just as only

Nixon could open China, only Eastwood could smuggle paralyzing doubts into the

underrated ‘American Sniper’; his war films ‘Flags of Our Fathers’ and ‘Letters

from Iwo Jima’ are remarkably critical. ‘The 15:17 to Paris’ won’t help his

defenders. Perversely, you wait (and wait) for the train attack, hinted at in

flurries of flash-forwards. It’s over in an instant: competently staged but

coolly played. Eastwood makes the film feel like a rote assignment: an act of

patriotic duty trying to pass as drama. Already we’ve heard several times,

ominously, about the 'greater purpose' these guys are 'catapulting' toward

(seriously, the script is that dull-witted). Even if it weren’t already set on

a track, the movie has only one way forward: a straight line into mundanity.

Three Average Guys Make The 15:17 to Paris worth watching,

by STEPHANIE ZACHAREK, Time magazine, February 8th, 2018

The stars of The 15:17 to Paris, directed by Clint Eastwood,

aren’t movie stars at all. They aren’t even actors. Instead, they’re a trio of

young men, friends from childhood, who in 2015 foiled an attempted attack on a

train from Amsterdam to Paris, subduing and disarming a man who had just opened

fire on passengers with an AK-47. In the movie’s tense climax, Spencer Stone,

Alek Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler–then a U.S. Airman, National Guardsman and college

student, respectively–re-create the moment in which they leaped to action

almost without thinking. It sounded brave enough when we all first heard about

it. But it’s even more remarkable as Eastwood renders it, and the men–all

charmers, with none of the stagy stiffness common to nonactors–bring that

moment to life so vividly that its very casualness is a jolt.

That’s the best part of the movie. The second best are the

scenes in which the three friends, before boarding that train, knock around

Europe–they’re just regular dudes on vacation, kicking back steins of beer and

hoping to meet pretty girls. (With their selfie sticks and well-mannered

bonhomie, they’re the kind of Americans whom Europeans claim to dislike but

secretly love.) The sections detailing the men’s childhood in Sacramento, with

Judy Greer and Jenna Fischer playing beleaguered moms? Not so exciting. But

then, the very averageness of these conscientious, gutsy guys is precisely the

point.

No comments:

Post a Comment